November 2017

Guest Editor: Tali Hatuka

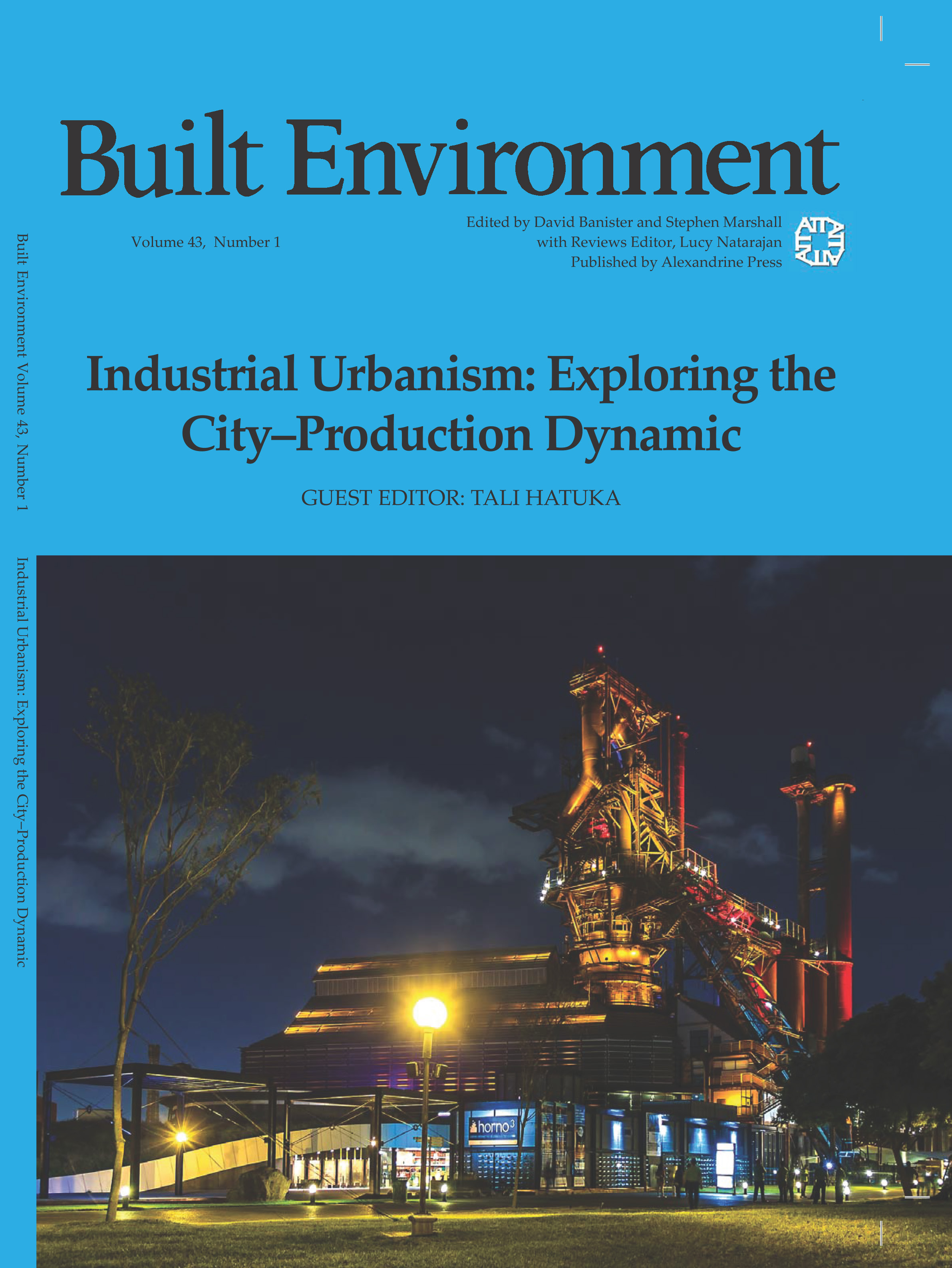

Built Environment

Since the Industrial Revolution, cities and industry have evolved together: from Manchester, England, to Rochester, New York, company towns and entire metropolitan regions have grown around factories and expanding industries. Despite this shared past, popular notions of manufacturing tend to highlight industry’s negative aspects: pollution, environmental degradation, and the exploitation of labor caused by expanding industry, on the one hand; and blight, abandonment, and “shrinkage” resulting from the more recent decline of manufacturing in cities in the developed world, on the other

Industrial Urbanism moves the conversation beyond the negative, exploring the relationship between current urban planning practices and the places where goods are made todayIn a time of dramatic shifts in the manufacturing sector — from mass production to small-scale distributed factories; from polluting and consumptive production to a clean and sustainable process; from a demand of unskilled labor to a growing need for a more educated and specialized workforce — cities will see new investment and increased employment opportunities. Yet, to reap these benefits will require a shift in our thinking about manufacturing.

In the quest to makes cities competitive and resilient, we should ask: What are the contemporary relationships between city and industry? What might future relationships between city and industry look like? What physical planning and design strategies should cities pursue to retain, attract, and increase manufacturing activity?

These questions point to the limitations of the current planning and architectural paradigm in addressing manufacturing, and the need to conceptualize new planning strategies that would respond to and help cities adapt to current trends in manufacturing. Spatial adaptation to manufacturing is required at the regional, city and local scales, in both existing and new settings, and taking into account, not merely the physicality of space, but also its social and political characteristics.

This is not a simple task. In a society widely perceived as “post-industrial,” it is essential to educate the public about manufacturing processes. A deeper awareness – a true consciousness-raising – is necessary if we are to dispel lingering misconceptions that portray industry as always unsafe and polluting and instead, present manufacturing as an appropriate and even desirable activity within the city. When industrial processes were most noxious, factories moved out of the city and into windowless, suburban boxes. The animosity was mutual: manufacturers were as content to shut the public out as the public was to banish them from their downtowns. This attitude must be altered if industry is to be welcomed back, to resume its role as a good (and productive) urban citizen. Manufacturers who take pride in their work will encourage the public to share in their fulfillment.

Thus, redefining the role of industry in our urban areas, making it an integral part of our cities, is a spatial, social and economic challenge. More than two centuries after the start of the Industrial Revolution, policy makers, planners and designers have an opportunity to reconsider the ways industry creates places, sustains jobs, and promotes environmental sustainability. This is the future of manufacturing. This is the future of our cities.